|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

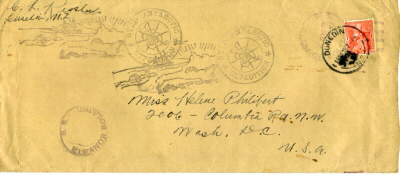

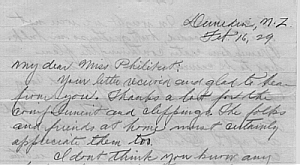

| Dunedin, N.Z. Feb. 16, 29 |

| My dear Miss Philibert: Your letter received and glad to hear from you. Thanks a lot for the compliment and clippings. The folks and friends at home must certainly appreciate them too. I don't think you know any of the other Washingtonians. Charlei Lofgren is on the "City of New York". A few sidelights on the recent trip to the "Barrier" might prove interesting. Our good friends in New Zealand were wagging their heads when we shoved off and many said we were slated for a "watery grave". In all fairness to them, we must admit that our ship looked anything but sea-worthy. Our cargo was perhaps the most general one ever shipped. It consisted of everything from toothpicks to to aeroplanes. In weight we were not greatly overloaded, but greatly so in bulk. Tremendous crates containing the planes had to be carried on deck and this called for a super-job of lashing down. Every passageway was completely filled with gas-drums and acetylene tanks. You had to do the juggling act when moving fore and aft. That was not all, our cargo consisted of everything imaginable in the way of explorers. Gas was carried in the hole and hatch covers had to be removed every day to allow ventilation. Smoking-lamp was out. All this weight proved mighty handy later on. Things went well for the first few days and then we ran into heavy weather. Our deck cargo began to slip in spite of the lashing and the situation was anything but pleasant with heavy seas running. We did all that was possible and she weathered the gale with flying colors. All hands were now looking forward to the icepack. Having recently towed the "City of New York" to the ice, the pack was no novelty, but we were thirsting for a crack at it. Having beaten the "City" so unmercifully in the race to Dunedin, they were anxious to get something on us and thought they had found it. They nicknamed our ship the "Little Tin Ship" and were so sure we were going be crushed in the ice that they were wishing us all kinds of good luck on the ice after she had sunk. Here's where our heavy cargo load came in and we smashed our way through 300 miles of ice in three days. The jolting and scraping (now full ahead and then astern and so on) were very annoying at first, but when you're really tired, you soon sleep in spite of these handicaps. The trip through was anything but monotonous, because here and there a seal could be seen bopping and then a flock of penguins, with their little wings flapping and squawking in great glee. We emerged from the ice at 74° south and except for large bergs we had open water from then on. The large bergs are never found in the pack. The undercurrents carry them and they plow through the pack ice like a steam driven vessel. We were not many days in sighting the great ice-barrier and it reminded me of the chalk-cliffs of Dover. On our return trip from Spitzbergen we passed there. Only a couple of hours more and we were entering the "Bay of Whales". The bay runs back about seven miles and is open water at this season with the exception of tremendous bergs that break off the barrier and pan-cake ice that forms overnight. The "Bay of Whales" is the only possible name that could have been given it. Our first problem was to find a suitable place to discharge our cargo and time was and still is precious. A dandy place was found with a natural runway up to the barrier and we were soon pounding our way through the bay ice in order to get close enough in. Some of the bigger boxes weighed over two tons and Comdr. Byrd was a bit afraid to unload this weight on the bay ice. Remember, it was the "Little Tin Ship" and not the famed ice-breaker that made this passage through the ice possible. We were soon moored fast to the ice and unloading began in earnest. It was necessarily slow however, because the gear had to be pulled or dragged back to safety for fear the ice might carry away. Things moved so orderly that Comdr. Byrd decided to stack up the cargo on the ice. This would speed up unloading considerably but might prove costly if the ice broke. That is exactly what happened and while we have been lucky from the start, this was the first of several breaks of a lifetime. The center-section of the "Ford" plane and other miscellaneous gear was on the ice and she started cracking in all directions. These cracks soon widened into crevasses and had one occurred directly under the wing-section or some of the men working, it would have been costly to the expedition. This is the plane especially built for long flights, such as to the pole and back. The other planes would have to be refueled at an advanced base. The crevasses widened into small canyons and a once splendid dock became a mass of individual bergs. The lines from the ship were made fast in the barrier itself, and this saved the day. This prevented the ice from drifting entirely free and eliminated the danger of individual bergs capsizing. There was that frail looking part of a wing, lying on the ice and had it slipped into one of the many cracks, not only a $50,000 plane would have been useless, but a $1,250,000 expedition would have received a terrible set back. We managed to get to it by using planks and in this way we dragged it out of danger and safely aboard. Everybody worked fast and only one dog sled and a few bags of coal were lost. We pulled out into the bay and when the ice had drifted clear we came alongside the barrier and once more our anchors were buried in the snow. There was quite an overhang to the barrier at this point, but it was the best available, because of the height. The barrier was fifteen ft. higher than the ship's side and this didn't speed matter up any. The average height is about 50 or 60 feet at the edge and increases to 90 or 100 ft. as you go inland. We were getting along famously and had just unloaded and handed the fuselage of the "Ford" plane back to comparative safety, when the big slide came. Two men were caught near the edge and came down with it. One, a Washingtonian, named Henry Harrison, a meteorologist from the weather-bureau, was lucky and grabbed a rope. Anything might have happened to him and he is all smiles today. The other chap, a technical-sergeant of the Army, by the name of "Roth", got his money's worth and the coldest bath of his life. He was fortunate in not getting crushed or drowned between the ship and the ice. Comdr. Byrd and two other fellows dived in to his aid and a boat was lowered and all were fished out, none the worst for their experience. After a good rub-down and a change of clothing they were back on the job. The falling ice nearly capsized our ship and were it not for the lines to the "City of N.Y.", I believe she might have gone over. I was standing on the fo'c'sle when it happened and had a wonderful view of the slide and effect. Everything considered, the conduct of the crew was wonderful. The ice continued to cave in and the ships had to get away. We pulled well into the bay ice and discharged the remaining cargo onto the deck of the "City". Time is everything and we were immediately underway for Dunedin to reload and return. The planes were assembled there and taxied over to the base. The many tons of coal, stores and other gear were carried on "Dog" teams. The dogs have been worth their weight in gold. Nine dogs to a ton load. Twenty-seven recently pulled a load of 2 1/2 tons for the whole six miles. The dogs love nothing better than to fight and will kill each other if not stopped. We have a 3/4 wolf in the pack and at times he is all wolf. Several houses have been built and two radio towers (50 & 60 ft.) have been completed. The flying field is not a problem like up north and one can be found most anyplace. The barrier rolls slightly, but is remarkably smooth and resembles a great white desert. There is a haze here at times but no fog. The aviators chief concern in this region is the wind. Oh boy, but it can howl. There is probably less wind at the Bay of Whales than other place in the Antarctic, but plenty for two windmills. Animal and Bird life is limited indeed. Whale and seal in the mammal line and the "Skua" gull in the bird. The Skua gull lives mostly on the eggs of penguins. We have the ice-bird too and the penguin which I believe comes under the heading of sea-fowl. Seal is plentiful and we only kill enough for food. The fellows don't howl much for it but the dogs do. It has a vinegar taste to me. Killing them is plain murder--you simply have to walk up and knock them in the head. They weigh as high as 500 lbs. The "Killer Whale" makes his home here and they can be seen in every direction, blowing and diving. This type of whale is more ferocious than man-eating sharks and will overturn boats or small ice floes to get at you. This is the method they adopt in catching seal. The seal often sleep on the ice. The funniest of all is the penguin. They look like a group of waiters in their black coats with their white breast. They walk very erect and with a stiff leg-motion like a kid on stilts. Their wings are very much underdeveloped and they cannot fly. They dive into the water like a person and can really make knots. They swim like a porpoise--in a series of dives in order to breathe. Hope to have more news from the barrier next time. I shall never forget our trip coming home as we call Dunedin. The people here are much on the American line and have been so hospitable during our stay here that it really seems like home. If we accepted all the invitations we receive we would have little time for anything else. We coaled ship from the C.A. Larsen, a whaler from Norway, on our way north and were interested on-lookers at that sea-going factory. They can cut up a whale weighing 20 tons in forty-five minutes and have him in the vats. We were a week making the last 1000 miles and it was the roughest I have ever experienced. Our ship was absolutely empty and what she didn't do I have no desire to experience. Food could not be served on the table and sleeping was postponed. All hands were a little tired when we arrived. They are working overtime in order to get loaded and get away. A ship should never be in the bay after March 1st. and we must hurry. Hoping this finds you well, I am |

| Sincerely yours, Chas. Kessler Byrd Antarctic S.S. Eleanor Bolling Dunedin, N.Z. |

|

P.S. If you have remained awake throughout this volume you are very patriotic. Our address will continue Dunedin for the next month or six weeks. All the men will not stay on the ice. Because of the food supply, only a limited number and when the aviation, scientific, radio, medical and a few flunkies are counted there's no more room. The remainder will probably winter at Auckland. This is not official yet. Tell Mr. Whentley our radioman complains of the static around the Navy Dept. Best regards to all. Please overlook mistakes, writing and untidiness. Have written hurriedly. We are working 6 hrs. on & 6 off. At sea over a month, in past 36 hrs. then at sea over a month. [Next] Postal History: Highjump / Windmill / Deepfreeze Home Page Antarctic Philately [Contents] Antarctic Philatelic Website Contents |