|

|

Back to Page

3

Intervening Years &

the

Voyage of

the

Quest

As

Shackleton returned to England, in May of 1917, the war

continued to rage on in Europe. At 42 years of age,

Shackleton was one year beyond conscription age. Even though

authorities were lowering acceptance standards, joining the

Army meant a medical exam; under no circumstances would he

allow Army doctors to listen to his heart. Meanwhile, more

than 30 members of the Trans-Antarctic Expedition, from both

the Weddell Sea and Ross Sea branches, were fighting with

the forces. McCarthy, who had survived the open-boat

journey, had already been killed at sea. Possibly fearing

rejection by the medical doctors, his attention turned

elsewhere.

By August 1917, Shackleton was

bombarding the War Office with offers to go to France to

serve on front-line transport. He tried the Foreign Office

for a mission to Italy. But all attempts resulted in

failure. He was drinking a little too much and his

appearance was of a man aged well beyond his years.

Shackleton was introduced to Sir Edward Carson, an

Anglo-Irishman who had just become Minister without

Portfolio in Lloyd George's War Cabinet. Carson,

dissatisfied with the conduct of the war in general and

propaganda in particular, dispatched Shackleton to South

America where propaganda was notably inept. Shackleton

sailed for Buenos Aires, via New York, on October 17, 1917.

German U-boats were sinking 300,000 tons of British shipping

every month but even they couldn't stop Shackleton

from his new mission. Immediately upon arrival in Buenos

Aires, Shackleton dove into his work. "Dispatch no more

propaganda literature to Argentine", Shackleton wrote back

to London. He had found twenty tons of outdated printed

matter collecting dust in warehouses around the city.

Shackleton decided to aim his efforts at persuading the

governments of Argentina and Chile to forsake neutrality and

enter the war on the side of the Allies. It was all to

little effect. In January 1918, Shackleton lost his patron

in London when Carson resigned over Home Rule. Shackleton

left Buenos Aires in the middle of March to return to

London, via Santiago, Panama and the United States. When he

arrived in London at the end of April, he was given the cold

shoulder. There simply was no place in the official

hierarchy for an amateur diplomat.

Shackleton

now became involved in an undercover enterprise. A company,

the Northern Exploration Company, was preparing an

expedition to Spitsbergen. Shackleton was asked to be the

leader. Ostensibly, the company was going to mine mineral

claims owned since 1910 by the company. Since 1910 the

Germans had a meteorological station at Ebeltofthaven in

West Spitsbergen, which was only withdrawn at the start of

the war. Spitsbergen was a delicate issue as it was

administered by Norway, a neutral country. With the backing

of the British Government, the Northern Exploration Company

could establish a British presence on the islands. To prove

it's commitment, the government provided the expedition with

an armed merchant ship, the Ella. Frank Wild, now

commissioned as a temporary lieutenant in northern Russia,

was selected by Shackleton as his assistant.

By the middle of August, Shackleton

was in northern Norway, at Tromsø, on his way to

Spitsbergen; it was the first time he had crossed the Arctic

Circle. It was in Tromsø that Shackleton suddenly

became ill. He "changed colour very badly", as McIlroy put

it. He suspected a heart attack. Shackleton refused to

undress so McIlroy could listen to his heart. This was the

first hint that Shackleton might be suffering from heart

disease. Shackleton had to turn back, arriving in London in

early September. Meanwhile, the leadership of the expedition

was placed under Frank Wild.

The

northern Russia campaign, said General Ironside, "was a side

show of the Great War". Soldiers could hardly be spared from

the front lines so troops were scraped from the bottom of

the barrel to be sent to Russia. At this point, no one was

going to worry about the condition of Shackleton's heart.

Early in October Shackleton sailed for Murmansk. As

Shackleton wrote, it was a "job after my own heart...winter

sledging with a fight at the end". As he crossed the Barents

Sea, he wrote to Janet Stancomb-Wills, "All is sheer beauty

and keen delight. The very first...snow-squalls bring home

to us the memories of our old South Lands. There is a

freshness in the air, a briskness in the breeze that renews

one's youth". "This day 3 years (ago) the 'Endurance' was

crushed in the ice," Shackleton wrote to his younger son

Edward, on October 26, "and we all were...sleeping on,

rather moving about on, the moving ice with no home to go

to. I have been to many places since then, now it is the

other end of the world". Shackleton had just landed at

Murmansk.

A fortnight later, on November 11, the

Armistace was signed. The war with Germany was over.

However, war in northern Russia was not yet at an end; the

Allied forces were now fighting the Bolsheviks instead. The

north Russia force had attracted various polar explorers:

Macklin, Worsley and Hussey from the Endurance

Expedition; Stenhouse, from the Aurora branch of the

Trans-Antarctic Expedition; Victor Campbell, the leader of

Scott's Northern Party; Dr. Edward Atkinson, from the Scott

camp and Dr. Eric Marshall from the Nimrod

Expedition. Shackleton's official job description was "Staff

officer in charge of Arctic equipment". In all actuality, he

was a glorified storekeeper. He had done most of his work in

London and the outfits he now provided were doubtful; his

own expeditions had been struggles against poorly designed

equipment and clothing. The American troops in the region

discarded the Shackleton clothing and boots and reverted to

their own. Shackleton was now kept at headquarters in

Murmansk with little to do.

Shackleton wrote to Emily, "I have not

been too fit lately. I am tired darling a bit and just want

a little rest away from the world and you". The strain of a

divided self was showing itself in Shackleton. "I am

strictly on the water wagon now", he wrote to Emily at the

end of January, 1919. He got thoroughly drunk on Christmas

Day and, in his own words, "after a thought I have cut it

right out it does me no good and I can tell my imagination

is vivid enough without alcohol it makes me extravagant in

ideas and I lose balance...I did not upset my superiors

everyone was awash only it seems to take different people

different ways. If I had not some strength of will I would

make a first class drunkard". Shackletons' affairs were in a

poor state; money was in short supply. Emily was fending for

herself while Cecily was at Roedean and Ray, the eldest boy,

was at Harrow. Shackleton hoped to cover the school fees

from selling shares of his stock in the Northern Exploration

Company, but the transaction never happened.

By the end of March, 1919, Shackleton

was back in London and demobilized after five months in the

field. He was regarded well enough by The Times that

an interview was requested. In that interview, Shackleton

stated that nearly half a million people "threw in their lot

with us...against the Bolshevist menace. It is thus not

merely a question of saving our own troops, but a moral

obligation to civilization...No domestic or political

consideration should be allowed to interfere with steps

being taken immediately to prevent anything in the nature of

a reverse to our arms in these regions...In Murmansk, as

elsewhere, the peasant is not a Bolshevist...but without

armed support he is helpless...do not let us be too

late...the British people do not yet realize what Bolshevism

means...it is...becoming far worse than German

militarism".

The Quest

Expedition

Shackleton

was now reduced to lecturing on the Endurance

Expedition. From December 1919 until May 1920 he appeared

two times a day at the Philharmonic Hall in Great Portland

Street. It was extremely boring to him and, besides, little

money was raised as he often lectured to half-empty houses.

The legend of Scott and his heroic but tragic march to the

Pole was more the spirit of the times. At the Hall,

Shackleton gave live commentary on Frank Hurley's silent

film of the expedition. Images twice each day were presented

on the screen, Shackleton having to live again and again

through the death of all his dreams. Shackleton was repelled

by the thought of working on the book of the expedition but,

at the end of 1919, it appeared as South. The text

was originally dictated to Saunders in New Zealand and

Australia in early 1917. Shackleton had not touched the work

and lacked the money to pay Saunders. The chronometers

brought back by the Ross Sea Party were sold and the

proceeds given to Saunders. Leonard Hussey did the final

editing, without payment.

The critics, in general, praised

South. Apsley Cherry-Garrard, who had been with Scott

and was now promoting his own work, The Worst Journey in

the World, praised the work. In his review of

South Cherry-Garrard wrote of a comparison between

Shackleton and Scott (two losers, in his opinion, with

Amundsen the clear winner), "Do not let it be said that

Shackleton has failed...No man fails who sets an example of

high courage, of unbroken resolution, of unshrinking

endurance. Explorers run each other down like the deuce. As

I read with a critical eye Shackleton's account of the loss

of the Endurance I get the feeling that he...is a

good man to get you out of a tight place. There is an

impression, of the right thing being done without fuss or

panic. I know why it is that every man who has served under

Shackleton swears by him. I believe Shackleton has never

lost a man: he must have had some doubts as to whether he

would save one then. But he did, he saved them every one.

Nothing is harder to a leader than to wait. The unknown is

always terrible, and it is so much easier to go right ahead

and get it over one way or the other than to sit and think

about it. But Shackleton waited...and waited, it seems quite

philosophically...Through it all one seems to see Shackleton

sticking out his jaw and saying to himself that he is not

going to be beaten by any conditions which were ever

created. Shackleton had always given an impression of great

grip--I should watch with joy the education of a shirker who

served under the Boss.

A picture haunts my mind--of three

boats, crammed with frost-bitten, wet, and dreadfully

thirsty men who have had no proper sleep for many days and

nights. Some of them are comatose, some of them are on the

threshold of delirium, or worse. Darkness is coming on, the

sea is heavy, it is decided to lie off the cliffs and

glaciers of Elephant Island and try and find a landing with

the light...Many would have tried to get a little rest in

preparation for the coming struggle. But Shackleton is

afraid the boat made fast to his own may break adrift...All

night long he sits with his hand on the painter, which grows

heavier and heavier with ice as the unseen seas surge by,

and as the rope tightens and droops under his hand his

thoughts are busy with future plans". South sold well

but Shackleton earned nothing from it. None of the money

borrowed for the Endurance Expedition had been repaid

and most of his benefactors had written off their loans. One

exception was Sir Robert Lucas-Tooths' heirs; his executors

required Shackleton to repay the loan and since his only

asset was the book rights, in settlement he assigned all

rights to them.

Shackleton was drinking heavily again. He was also smoking

and eating too much. He was putting on weight and was

constantly hit with colds and fevers, and what he called

"indigestion", which meant severe pains across his shoulder

blades. As for money, he still had none. In the spring of

1920 he began expressing a desire to see the polar regions

just one more time. In August 1920, taking Emily's advice,

Shackleton wrote to Teddy Evans, now Captain E.R.G.R. Evans,

DSO. Shackleton wrote, "I know you have always been a good

friend to me; that there is not a spark of jealousy or

backbiting about you, that both publicly and privately you

have always boosted my work and myself, and stood by me so

that I count you a real friend. This is no balderdash or

gush on my part". Since taking part in Scott's second

expedition, Evans had bitterly disliked Scott. He had

befriended Shackleton, and in a rebuttal of Scott's constant

belittling of Shackletons' achievements he wrote, "Those of

Captain Scott's followers who made...the ascent of the

Beardmore Glacier, were amazed at Shackleton's fine

performance...His descriptions were so easy and so careful

that every landmark was recognised...We easily saw from the

copies of his diary, which we carried along, where we might

look for coal and other interesting geological

specimens...on the plateau we met with just the conditions

he had described...we used his splendid charts, and

generally benefited by his praiseworthy pioneer work.

Indeed, Shackleton and his companions set up a standard that

was extremely difficult to live up to, and impossible to

better".

"Now",

Shackleton wrote, "my eyes are turned from the South to the

North, and I want to lead one more Expedition. This will be

the last...to the North Pole...Amundsen, I know from the

Siberian side is planning to reach the North Pole. Why

should I not get there before him?" Financing was once again

an issue. Shackleton visited Canada and obtained the

co-operation and financial backing from several prominent

Canadians along with a promise of aid from the Canadian

government. Shackleton now proceeded to gather a core group

of experienced men and a hundred sledge dogs. While busy in

preparing for the expedition, the Canadian government

suddenly withdrew their support. At this critical point, an

old school friend, John Quiller Rowett, came to the rescue.

Rowett was an independently wealthy man, a man of many

interests in scientific affairs. He was particularly

instrumental in the founding of the Rowett Institute for

Agricultural Research in Aberdeen. Rowett agreed at first to

only finance part of the expedition but in the end agreed to

pay for almost everything himself. Shackleton, once more,

promised repayment out of future lectures, films and a book.

But it was now too late for the Arctic

that year so the Northern Expedition was cancelled.

Shackleton could not bare to wait any longer so he swung his

attention from the north to the south. He would use the

Antarctic summer to go south instead and, fortunately,

Rowett generously agreed. Since little time was left, the

dogs were cancelled as not being needed and the program

turned to concentrate on observation and scientific data

rather than the making of a prolonged land

journey.

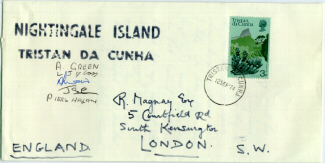

The

route was to be St. Peter and St. Paul's Rocks on the

Equator, South Trinidad Island, Tristan da Cunha and the

nearby islands of Inaccessible, Nightingale and Middle

Island, Gough Island and then on to Cape Town which was to

be the home base for operations in the ice. From here, the

route would lead eastward to Marion Island, Crozet Island,

Heard Island and then through the ice generally westwards to

emerge at South Georgia.. From here, they would head back to

Cape Town to resupply and refit the ship for the return

journey via New Zealand, Raratonga, Tuanaki Island,

Dougherty Island, the Birdwood Bank and home via the

Atlantic. The

route was to be St. Peter and St. Paul's Rocks on the

Equator, South Trinidad Island, Tristan da Cunha and the

nearby islands of Inaccessible, Nightingale and Middle

Island, Gough Island and then on to Cape Town which was to

be the home base for operations in the ice. From here, the

route would lead eastward to Marion Island, Crozet Island,

Heard Island and then through the ice generally westwards to

emerge at South Georgia.. From here, they would head back to

Cape Town to resupply and refit the ship for the return

journey via New Zealand, Raratonga, Tuanaki Island,

Dougherty Island, the Birdwood Bank and home via the

Atlantic.

The goal was to circumnavigate the

Antarctic continent, looking for "lost" or uncertain

sub-Antarctic islands. He wanted to look for Captain Kidd's

treasure on South Trinidad in the Atlantic and for a certain

pearl lagoon in the South Seas. Also, he wanted to

determine, "once and for all, the history and methods of the

Pacific natives in their navigation across the Pacific

spaces hundreds of years before Columbus crossed the

Atlantic". The vessel in which they sailed was in pitiful

shape and uncomfortable. Shackleton purchased her in Norway

at the beginning of the year. She was a wooden sealer of 125

tons originally called the Foca I. At Emily's

request, she was renamed the Quest. A baby "Airo"

seaplane, the first plane to be used in polar exploration,

was carried aboard.

The

Quest was refitted at Hays Wharf and on September 17,

1921, from St. Katharine's Dock, under Tower Bridge,

Shackleton finally sailed. The Quest had been

intended for the Arctic expedition and was not suited for a

long, trans-oceanic journey. She lumbered heavily in the

trade winds, her engines too weak. Out at sea her boiler was

found to be cracked. She needed repairs at every port of

call. Against all this, Shackleton seemed to fight as he had

always fought. Shackleton wrote to Janet Stancomb-Wills from

Rio de Janeiro, "The years are mounting up. I am mad to get

away. If I knew you less well I would not write like this

but I want to open up...we...go into the ice into the life

that is mine and I do pray that we will make good, it will

be my last time I want to write your good name high on the

map and however erratic I may seem always remember this,

that I go to work secure in the trust of a few who know me

and you my friend not least among them".

The expedition seemed to have a

beginning but, conversely, no end. The expedition geologist,

Vibert Douglas, "hoped to find some mineral deposit that

would get him out of his financial straits". The cameraman,

an Australian named George (later Sir Hubert) Wilkins,

believed this voyage was "to be a long, but not entirely

selfish joy ride...a last expedition (Shackleton) was

determined to have". Dr. Macklin wrote, "There is something

different in him this trip as compared with the last which I

do not understand". It was late December and they were being

tossed about in the South Atlantic on their way to South

Georgia. On board Quest, Shackleton was constantly

ill. His broad face was pale and pinched. At Rio de Janeiro,

Shackleton had a massive heart attack but, as usual, refused

to be examined. Macklin knew he was suffering from heart

disease.

All the physical problems which

Shackleton had tried so hard to hide were now falling into a

pattern. It went back at least three years to the suspected

heart attack during the Spitsbergen expedition; at the time

Macklin simply thought it angina. Shackleton was noticeably

drinking more. He drank champagne in the morning, possibly

to ease the pain. Against Macklins' orders, Shackleton

insisted on staying on the bridge four nights in a row

during a storm. More than anything else, Shackleton's mental

changes troubled Macklin. He had no plans, and the only

certainty was that South Georgia was to be their first port

of call after leaving Rio. A great deal of the time was

spent listening to Hussey strumming his banjo, the same

banjo he had on Elephant Island. "The Boss", Macklin wrote

on December 31, 1921, "says...quite frankly that he does not

know what he will do after S. Georgia. I do not understand

his enigmatical attitude". Another of the men on board,

James Dell, was suddenly confided in by Shackleton. Dell,

his old messdeck friend from Discovery, held similar

views of Scott. After all the years, Shackleton still burned

with resentment at the way Scott had made him publicly give

up rights to McMurdo Sound, and thus forced him to break his

promise when he sailed there on the Nimrod after all.

That was the albatross around his neck.

Finally,

on January 4, 1922, the Quest came within view of

South Georgia. "Like a pair of excitable kids", said

Worsley, he and Shackleton "were rushing around showing

everyone where we first came over the mountains on our 1916

tramp across S.G. from King Haakon (Bay) to Stromness Bay

after our boat journey from Elephant Id. Finally the 'Boss'

called me when I was on the bridge to come & show some

of the others a point he wasn't quite sure of, but I

couldn't leave here at the time & came down later, but

the dear old 'Boss' was quite prepared for me to let the

ship wander along on her own". The Quest anchored

outside the whaling station of Grytviken; it had been eight

years since Shackleton had sailed up the same fjord in

Endurance on his way to the Weddell Sea.

Surprisingly, many of the same old faces were there.

Fridthjof Jacobsen was still station manager. He came out in

a boat and took Shackleton ashore. Macklin was not surprised

when in the early hours he was called to Shackleton, and

found him in the midst of another heart attack. Macklin, as

many times before, told him he would have to change his

style of life. Macklin said that Shackleton replied, "You're

always wanting me to give up things, what is it I ought to

give up?" A few minutes later, in the wee hours of January

5, 1922, Shackleton was dead.

Shackleton's

body was to be sent back to England for burial. With it went

Hussey, who had no heart for the expedition now that his

leader was dead. When Emily heard what had happened, she

decided that her husband should be buried on South Georgia.

His spirit had no place in England...if he had a home on

earth, it must be among the mystic crags and glaciers of the

island in the Southern Ocean which had meant so much to him.

So from Montevideo, Hussey turned around and brought the

body back to South Georgia. There, on March 5, he was laid

to rest in the Norwegian cemetery, along with the whalers

amongst whom he had felt at home.

|

|

![]()