|

|

Back to Page

1

The Terra Nova

Expedition 1910-13

On

January 28, 1907 Scott wrote to the secretary of the Royal

Geographic Society, Mr. Scott Keltie, requesting financial

assistance (£30,000) for a second expedition to

Antarctica. He was already in touch with Barne, Mulock and

Skelton of the Discovery expedition. Unfortunately,

Ernest

Shackleton announced on

February 12 that he was pressing forward with his own plans

to lead an expedition to the South Pole. He had already

raised £30,000 and was soliciting the RGS for help as

well. Now the RGS felt caught in the middle which led to a

huge rift between Scott and Shackleton that was never to be

closed. A Clydebank shipbuilder, William Beardmore, had

agreed to guarantee funding for Shackleton with the money to

be repaid on Shackleton's return by writing a book,

lecturing and selling articles. Shackleton tried to persuade

Mulock to join him but Mulock declined because he had

already committed to Scott. This caught Shackleton by

surprise as he had no idea that Scott was planning on a

return expedition. Dr. Wilson was also approached by

Shackleton but likewise declined as he was in the middle of

an exhaustive project concerning his bird research in

Antarctica; it just wouldn't be appropriate to abandon his

studies at this time.

The day after Wilson received the

request from Shackleton, a letter showed up from Scott in

which he was curious if Shackleton had mentioned his own

desire to return to McMurdo Sound. This was the first Wilson

had heard of Scotts' plans. Scott was clearly upset for

essentially one basic reason: the view that an explorer may

have an exclusive right to his own territory was an unspoken

given. As the Frenchman Jean Charcot said, "There can be no

doubt that the best way to the Pole is by way of the Great

Ice Barrier, but this we regard as belonging to the English

explorers, and I do not propose to trespass on other

people's grounds". Shackleton had announced that he intended

to make his winter quarters at McMurdo Sound, an

announcement that should have been respectfully cleared

through Scott first. The courtesy was never extended to his

former commander. Nevertheless, Scott made an effort to not

let his personal feelings stand in his way as he wrote Scott

Keltie on March 1 and told him, "..it is our duty to work

together as Englishmen, I mean you, I and Shackleton and all

concerned. The first thing is to defeat the foreigners.

Whether Shackleton goes or I go or we both go, we must let

Arctowski clearly understand that the Ross Sea area is

England's and we will not appreciate designs on it". On the

other hand, Dr. Wilson wrote Shackleton, "I think that if

you go to McMurdo Sound, and even reach the Pole, the gilt

will be off the gingerbread, because of the insinuation

which will almost certainly appear in the minds of a good

many, that you forestalled Scott who had a prior claim on

the use of that base".

Shackleton and Scott met in London on

May 17, 1907 where Shackleton put in writing to leave

"McMurdo Sound base to you, and land either at the place

known as the Barrier Inlet or at King Edward VII Land,

whichever is the most suitable. If I land at either of those

places I will not work to the westward of the 170 meridian W

and shall not make any sledge journey going West...I think

this outlines my plan, which I shall rigidly adhere to, and

I hope this letter meets you on the points that you desire".

Scott replied, "Your letter is a very clear statement of the

arrangement to which we came. If as you say you will rigidly

adhere to it, I do not think our plans will clash".

Shackleton bought a small, dilapidated sealer, the

Nimrod, and attracted two former mates from the

Discovery expedition to join him, Frank Wild and

Ernest Joyce. The Nimrod sailed from the East India

docks on July 30, 1907, taking a motor car, the first to be

landed in Antarctica.

Scott

went back to sea as Captain of HMS Albermarle, a

battleship with a complement of over 700 men. His

appointment ended on August 25, 1907 and Scott went on

half-pay until his next appointment, on January 1, 1908, to

HMS Essex. It was between appointments that Scott

met, for the second time, a twenty-eight-year-old sculptor,

Kathleen Bruce. The two were invited to tea at Mabel

Beardsley's where Kathleen was struck by Scott's "rare

smile". Scott was hooked and for the next ten days he either

visited with her or wrote love notes: "Uncontrollable

footsteps carried me along the embankment to find no

light--yet I knew you were there dear heart--I saw the open

window and, in fancy, a sweetly tangled head of hair upon

the pillow within--dear head--it seems so long till

Friday--give me all the time you can". By the end of

November the two were engaged to be married.

Kathleen

Bruce

Although Con felt he owed his

mother his allegiance, Hannah wrote that "You must never let

me be a hindrance to your making a home and a life of your

own. You have carried the burden of the family since 1894.

It is time now for you to think of yourself and your future.

God bless and keep you".

Although Con felt he owed his

mother his allegiance, Hannah wrote that "You must never let

me be a hindrance to your making a home and a life of your

own. You have carried the burden of the family since 1894.

It is time now for you to think of yourself and your future.

God bless and keep you".

Meanwhile,

Shackleton and the crew of the Nimrod could not

penetrate the ice pack to reach King Edward VII Land so they

had to turn back and land the explorer's party at McMurdo

Sound. This broke his promise to Scott and as the

Nimrod steamed westwards, Shackleton wrote to his

wife, "I have been through a sort of hell since the 23rd

(January 1908) and I cannot even now realise that I am on

the way back to McMurdo Sound and that all idea of wintering

on the Barrier at King Edward VII Land is at an end--that I

have had to break my word to Scott and go back to the old

base, and that all my plans and ideas have now to be

changed--changed by the overwhelming forces of Nature...I

never knew what it was to make such a decision as the one I

was forced to make last night". Scott felt that this was

Shackleton's intention from the very beginning and thus felt

further betrayed.

Con and

Kathleen's courtship continued into 1908. Although he never

mentioned any attempt at the Pole, Kathleen wrote Con in

July 1908 asking him to "Write and tell me that you

shall go to the Pole. Oh dear me what's the use of

having energy and enterprise if a little thing like

that can't be done. It's got to be done, so hurry up

and don't leave a stone unturned--and love me more and more,

because I need it". Finally, on September 2, 1908, Con and

Kathleen were married in the Chapel Royal at Hampton

Court.

A

sailor's wife in those days was one to be pitied as husbands

were generally at sea for perhaps ninety percent of their

married life. The wife was left to maintain the home and

care for the children while the husband was away at sea,

presumably having a gay old time with his fellow sailors and

a wife in every port. This was a popular theory but in this

case, the opposite were true. Kathleen was living it up in

London with all her friends while making a name for herself

as a sculptor. Meanwhile, Con was living a lonely life as

captain aboard the Bulwark. But Kathleen had her

moments too, as she wrote Con in November 1908, telling him

she was as "desperately, deeply, violently and wholly in

love" as he was and was missing him terribly. "There's

something so terribly real about you. I used to mend your

trouser placquette hole and there's something grotesquely

real about that. I never used to know anything about

loneliness. Sir have you robbed me of my self-sufficiency?"

Early in 1909 good news finally arrived. Kathleen wrote, "My

love my dear love my very dear love throw up your cap and

shout and sing triumphantly for it seems we are in a fair

way to achieve my aim". Kathleen was pregnant. Also, an

opportunity arose for Con to spend nine months living at

home with his wife as an ordinary human. A position as Naval

Assistant to Admiral Sir Francis Bridgeman was offered and

accepted at the end of March 1909.

Also in

March 1909 the news came that Shackleton had not reached the

Pole. Despite all the hardships, Shackleton, Adams, Marshall

and Wild had crossed the Barrier, struggled up the glacier

which Shackleton named after his patron, Mr. Beardmore, and

planted the flag at 88°23'S, some 97 miles from the

Pole. Meanwhile, Professor Edgeworth David, Scott's surgeon

A. F. Mackay and Douglas

Mawson pushed on beyond the

point reached by Scott on his western journey in 1903 and

planted a flag on the South Magnetic Pole.

On July

1, 1909, Scott wrote Shackleton, "If as I understand it does

not cut across any plans of your own, I propose to organise

the expedition to the Ross Sea which as you know I have had

so long in preparation so as to start next year. I am sure

you will wish me success; but of course I should be glad to

have your assurance that I am not disconcerting any plans of

your own". Shackleton replied that his plans "will not

interfere with any plans of mine". On September 13, 1909,

Scott announced his plans: "The main object of the

expedition is to reach the South Pole and secure for the

British Empire the honour of that achievement". That very

same day a son, Peter, was born to Kathleen and Con. James

Berrie, a personal friend and the Scots playwright who wrote

"Peter Pan", and Clements Markham were chosen as the

godfathers.

On April

6, 1909, Robert Edwin Perry, a fifty-six-year-old commander

on leave from the US Navy, together with Matthew Henson, his

Negro servant and companion, reached the North Pole on their

sixth attempt. The North was won so all thoughts of polar

exploration now turned towards the South. Several nations

now commenced with preparations for the trek: Perry

announced in New York his plans to form an Antarctic

expedition with the goal of the Pole attained by embarking

from a region within the Weddell

Sea; Germany's Lieutenant Wilhelm

Filchner announced similar

plans as the Americans but with the added goal of being the

first to march right across the Pole in a trans-Antarctic

expedition ending in McMurdo Sound; Frenchman

Jean-Baptiste

Charcot was exploring regions

in Graham Land; the Japanese, led by Lieutenant

Nobu Shirase, planned an

expedition to the very region which Scott hoped to explore

in King Edward VII Land.

Scott

went to work to raise the needed £40,000 for the

expedition. Unfortunately, donations were slow in coming.

Sir Edgar Speyer, the City financier, became Honorary

Treasurer of the British Antarctic Expedition's fund and

donated £1,000. Touring the countryside giving lectures

to unenthusiastic audiences, Scott spent many cold nights in

cheap hotel rooms. "Between £20 and £30 from

Wolverhampton...£40 today...nothing from Wales...this

place won't do, I'm wasting my time to some extent...I don't

think there is a great deal of money in the

neighbourhood...things have been so-so here...I spoke not

well but the room was beastly and attendance small...another

very poor day yesterday, nearly everyone out", Scott wrote.

But, £2,000 came from Manchester, £1,387 from

Cardiff and £750 from Bristol.

In

November 1909 Shackleton got the knighthood Scott had missed

and his book, The Heart of the Antarctic, was

published.

In

January 1910 the Government announced a grant of

£20,000 and now the expedition could buy a ship. Scott

wanted the Discovery but the Hudson's Bay Company

refused to sell her. After considering several others, Scott

purchased the Terra Nova for a down payment of

£5,000 with a promise of an additional £7,500 when

the funds could be raised.

Experiments

with motor sledges were now under way. Michael Barne, still

dealing with frostbitten hands from the Discovery

expedition, had designed a new sledge. (Barne declined the

opportunity to join Scott and was married before the

departure of the Terra Nova). Early in March 1910,

Scott went to Norway with Kathleen, Reginald Skelton, two

mechanics and a "motor expert", Bernard Day, to test the

experimental sledges. While in Christiania, Nansen

introduced an expert skier, Tryggve Gran, to them. Gran was

planning his own assault on the Pole but dropped his plans

and joined Scott. Lieutenant Teddy Evans, who had talked his

way into his appointment in the Morning, had started

to raise funds for yet another expedition to the Pole. When

he heard of Scott's plans, he agreed to abandon his personal

desires and join forces with Scott provided he was offered

the position of second-in-command. Although Skelton was

deeply hurt, Scott could not refuse the offer as the funds

raised by Evans would be a real windfall. Evans was given

the charge of getting the ship prepared for the South. Upon

her return from the Discovery expedition, the

Terra Nova had been used for whaling and sealing and

was now in a filthy, stinking condition.

The Crew

Money

may have been slow in coming but volunteers were coming in

from all over the world. More than 8,000 men volunteered to

join the expedition. Five members of the Discovery

crew were accepted: Petty Officers Thomas Williamson,

Edgar Evans and Thomas Crean, also Chief Stoker William

Lashly and William Heald. The scientists were carefully

picked and from the onset, Edward Wilson was Scott's first

choice. Three geologists were chosen: two Australians, Frank

Debenham and T. Griffith Taylor, plus Raymond Priestley who

had been with Shackleton's Nimrod expedition.

Canadian Charles Wright was selected as the physicist while

George Simpson came from the Indian meteorological service.

The one physicist who didn't go was the young lecturer from

the University of Adelaide, Douglas

Mawson, who was making his own

plans, like many others, to explore an unmapped stretch of

coast and country west of Victoria Land. In a letter to

Griffith Taylor on February 15, 1910, Mawson wrote, "I am

almost getting up an expedition of my own...Scott will not

do certain work that ought to be done...I quite agree that

to do much would be to detract from his chances of the Pole

and because of that I am not pressing the matter any

further. Certainly I think he is missing the main

possibilities of scientific work in the Antarctic by

travelling over Shackleton's old route. However he must beat

the Yankees...". The biologists were Edward Nelson and D. G.

Lillie.

While

Wilson was selecting the scientists, Scott and Evans worked

on forming the rest of the crew. From the Admiralty came

naval lieutenants: Harry Pennell, navigator and magnetic

observer, Henry Rennick in charge of the hydrographical

surveys and deep-sea soundings and Victor Campbell. Two

Lieutenant-Surgeons, G. Murray Levick and Edward Atkinson,

were appointed along with twenty-six petty officers and

seamen. Various other volunteers were taken for a number of

reasons. Herbert Ponting was a skilled, experienced

photographer whose pictures taken during the Russo-Japanese

War and been published in leading magazines in Great Britain

and the United States. Apsley Cherry-Garrard, aged

twenty-four and a relative of Reginald Smith's, contributed

£1,000 to be appointed assistant biologist. Captain L.

E. G. Oates of the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, who walked

with a slight limp due to a wound received in the Boer War,

also contributed a similar amount and was put in charge of

the ponies as this was his area of expertise. Like Oates,

Henry Bowers, of the Royal Indian Marine, came from India to

join the expedition. Bowers, a Worcester cadet, was a

short, stocky man with red hair and a large nose which

quickly earned him the nickname Birdie. Another former cadet

from the Worcester, Wilfrid Bruce, joined the

expedition. This was Kathleen's thirty-six-year-old brother.

Bruce was instructed to travel to Vladivostok and meet up

with Cecil Meares who had just selected twenty Siberian-bred

ponies and thirty-four sledge-dogs for the expedition. The

animals were escorted to Lyttleton via Japan and Australia.

Losing only one pony and one dog on the long journey, the

animals were inoculated ten times and put ashore on Quail

Island.

Perhaps

Scott still retained fresh memories of the disastrous

results with the dogs during his southern journey on the

Discovery expedition, but whatever the reasons, his

transportation choices undoubtedly led to the expedition's

final results. The motor sledges were obviously

experimental, since none had ever been used before, while

the ponies would prove an even weaker link in the disastrous

chain of events. It is true that Shackleton took nineteen

ponies with him on his Nimrod expedition, but only

four survived to set out on the journey towards the Pole. Of

these, one had to be shot at the second depot; another gave

up at the third; and by the time they reached the foot of

the Beardmore Glacier only one was left. Soon afterwards,

this pony fell into a crevasse, leaving Wild, who had been

leading him, suspended by one elbow over the dark chasm.

Scott planned to use the sledges to motor across the Barrier

as far as possible, establishing depots along the way. The

ponies would then take over and haul the sledges to the foot

of the glacier. Scott felt that the animals would not be

able to make it up the glacier but would be a good source of

fresh meat upon their return from the Pole.

In retrospect, it is felt that Scott

would have had an easy go of it to the Pole had he

adequately trained men and dogs to make the assault.

Nevertheless, Scott wrote, "In my mind no journey ever made

with dogs can approach the height of that fine conception

which is realised when a party of men go forth to face

hardships, dangers, and difficulties with their own unaided

efforts, and by days and weeks of hard physical labour

succeed in solving some problem of the great unknown. Surely

in this case the conquest is more nobly and splendidly won".

On June 1, 1910, the Terra Nova was towed away from

the South-West India Docks as cheering crowds stood by.

Ponting, who was standing beside Scott, wondered what their

homecoming would be like and Scott answered, "I don't care

much for this sort of thing (as the crowds cheered and

steamers whistled). All I want is to finish the work we

began in the Discovery. Then I'll get back to my job

in the navy".

Kathleen and Con aboard

the Terra Nova

Scott did not sail with the

Terra Nova as he remained behind in an attempt to

raise additional funding. Scott, with his wife, left the

ship at Greenhithe where he was presented two flags by Queen

Alexandra, now the Queen Mother: one to be planted at the

farthest south attained while the second to be hoisted at

the same spot and then brought back. Scott stayed another

six weeks before leaving for South Africa to join the ship.

Kathleen made the difficult decision of leaving young Peter

behind and sailing on with Con as far as Sydney. They sailed

in HMS Saxon on July 16, 1910, and were seen off by

Wilhelm Filchner and Ernest Shackleton. Also aboard were

Edward Wilson's wife, Ory, and Teddy Evans wife, Hilda. They

reached Cape Town on August 2, 13 days before the Terra

Nova.

Scott did not sail with the

Terra Nova as he remained behind in an attempt to

raise additional funding. Scott, with his wife, left the

ship at Greenhithe where he was presented two flags by Queen

Alexandra, now the Queen Mother: one to be planted at the

farthest south attained while the second to be hoisted at

the same spot and then brought back. Scott stayed another

six weeks before leaving for South Africa to join the ship.

Kathleen made the difficult decision of leaving young Peter

behind and sailing on with Con as far as Sydney. They sailed

in HMS Saxon on July 16, 1910, and were seen off by

Wilhelm Filchner and Ernest Shackleton. Also aboard were

Edward Wilson's wife, Ory, and Teddy Evans wife, Hilda. They

reached Cape Town on August 2, 13 days before the Terra

Nova.

Like the Discovery, the

Terra Nova was a leaker. The leak wasn't too bad but,

nevertheless, everyone took a turn at the hand pumps

commencing at 6:00 a.m. and resuming every four hours around

the clock. When the ship reached the tropics, the heat was

incredible. After leaving Madeira, the winds became so light

that the engines were required. The men sweated and toiled

as they fed enormous amounts of coal into the three

furnaces. On July 25 the Terra Nova anchored off

uninhabited South Trinidad Island, some 700 miles east of

Brazil. (The Discovery had also visited the island in

1901, when a new petrel, named after Wilson ,Estrelata

wilsoni, was found). Wilson and Cherry-Garrard, armed

with guns, went after the birds; Lillie looked for plants

and rocks; Nelson and Simpson searched for fish in pools.

Five new species of spiders were collected and a new moth.

After leaving the island, the ship went "booming along"

before strong westerlies. They arrived in Simon's Bay, Cape

Town on August 15, 1910. The crew was soon reunited with

Scott and for the next few days each member was left to

himself to do as he pleased.

Although

not happy about it, Wilson was instructed to take an ocean

liner to Melbourne as Scott took over command of the

Terra Nova. Mrs. Scott, Mrs. Evans, Wilson and his

wife all sailed together aboard RMS Corinthic and

upon arrival in Melbourne, Wilson consulted with Professor

Edgeworth David and selected a third geologist. Meanwhile,

Scott was enjoying himself aboard the Terra Nova. The

object of taking command at Cape Town was to acquaint

himself with the crew and select the members of the two

shore parties; one party would remain at the expedition's

base of operations, in or near McMurdo Sound, carrying out

scientific research while the second party made the final

assault on the Pole. A splinter group of six men, called the

Eastern Party, was to be dispatched in unexplored King

Edward VII Land, four hundred miles to the east. This group

would be led by Victor Campbell. The naval lieutenants,

Pennell and Rennick, would remain in charge of the ship.

Scott wrote to his mother, "My companions are

delightful".

After

six weeks at sea, the Terra Nova reached Melbourne on

October 12, 1910. Wilson loaded the wives and a bag of mail

in a motor launch and set out to find the ship in pitch

darkness. Kathleen wrote in her dairy, as they approached

the ship "I heard my good man's voice and was sure there was

no danger, so insisted, getting more and more unpopular...We

at last got close to the beautiful Terra Nova with

our beautiful husbands on board. They came and looked down

into our faces with lanterns".

In

Scott's mail was a telegram sent from Madeira on September

9, 1910...a telegram from Amundsen

saying "Beg leave inform you proceeding Antarctic.

Amundsen". Scott was clearly troubled by this announcement.

Scott and much of the public resented the fact that

Amundsen's intentions appeared secretive in nature. He had

raised money for the publicly proclaimed intention of going

to the Arctic, managed to borrow the Fram from Nansen

without payment and then turned about face for the South

Pole. When the news arrived that Peary and Hansen had

reached the North Pole, Amundsen felt left with little

choice: "It was therefore with a clear conscience that I

decided to postpone my original plan for a year or two and

try to solve the last great problem...the South Pole".

Amundsen was heavily in debt and knew if there was any

chance to repay his debtors, a spectacular triumph would be

needed.

The Norwegians left Christiania on

August 9, 1910, with ninety-seven Greenland dogs, a hut in

sections and provisions for two years. When they arrived in

Madeira, only two members of the crew, his brother Leon and

the ship's commander, Lieutenant Nilsen, knew of his

intentions; the rest of the crew assumed they would be on

their way to Buenos Aires and then northwards to the Arctic.

At Madeira he informed the crew of his real plans and all

consented to go for the South. Amundsen chose to sail

directly for the Ross Sea, a non-stop voyage, so the

telegram for Scott was left with instructions for it not to

be sent until after the Fram had sailed. Once

Amundsen left Madeira, he vanished into the unknown.

Clements Markham put his spin on the situation when he

stated that "She (the Fram) has no more sailing

qualities than a haystack. In any case, Scott will be on the

ground and settled long before Amundsen turns up, if he ever

does". On October 15, 1910, Markham reported to the RGS

secretary that Amundsen had "quietly got a wintering hut

made on board and 100 dogs and a supply of tents and

sledges. His secret design must have been nearly a year old.

They believe his mention of Punta Aranas and Buenos Aires is

merely a blind, and that he is going to McMurdo Sound to try

to cut out Scott...If I were Scott I would not let them

land, but he is always too good-natured".

Scott,

still chasing money, went on to New Zealand, via Sydney, by

way of ocean liner. Meanwhile, Teddy Evans resumed command

of the ship as they left the harbor under full sail in full

view of the Admiral's 13,000 ton flagship and the rest of

the squadron. The Scotts arrived in New Zealand on October

27 and were greeted by Clements Markham's sister, Lady

Bowen, and her husband, Sir Charles. They stayed in

Lyttleton with the expedition's agent, Joseph J. Kinsey.

Kathleen wrote, "There we were for a happy fortnight working

and climbing with bare toes and my hair down and the sun and

my Con and all the Expedition going well. It was good and by

night we slept in the garden and the gods be

blest".

The

Terra Nova arrived and was promptly put into dry dock

in order to fix her leak. The ship had her stores rearranged

and repacked with everything getting banded: red for the

Main Party and green for the Eastern one. The scientific

instruments were checked and the hut was erected on land by

the men who would have the job of setting it up at winter

quarters. The three motor sledges, still in their crates,

were lashed to the deck. Oates argued for forty-five tons of

food for the ponies. (The ponies and dogs were waiting with

Bruce and Meares on Quail Island in Lyttleton Bay). Stalls

were built for nineteen ponies while the thirty-nine dogs

were chained to bolts and stanchions on the ice-house and

the main hatch, between the motor sledges. Scott managed to

get 430 tons of coal into the holds and 30 more tons stacked

in sacks on the upper deck. Oates managed to get an extra

two tons of fodder on board without Scott's knowledge. In

the ice-house were three tons of ice, 162 carcasses of

mutton, three of beef, and cases of sweetbreads and kidneys.

Scientific instruments were

everywhere: sledges, an acetylene plant, the wooden huts,

clothing, five ton of dog food and hundreds of other items

had to be squeezed in...there was hardly room for the men.

And, of course, there were other minor details. It seems

Petty Officer Evans got drunk again, as in Cardiff, and

disgraced the ship; and then the day before the final

departure from Port Chalmers, the other Evans came to Scott

with details of trouble between the wives. Tempers had

flared on the departure of their husbands and Oates reported

that "Mrs. Scott and Mrs. Evans had a magnificent battle,

they tell me it was a draw after 15 rounds. Mrs. Wilson

flung herself into the fight after the 10th round and there

was more blood and hair flying about the hotel than you see

in a Chicago slaughter-house in a month, the husbands got a

bit of the backwash and there is a certain amount of

coolness which I hope they won't bring into the hut with

them, however it won't hurt me even if they do". Once at

sea, all was well and later Kathleen stated, "If ever Con

has another expedition, the wives must be chosen more

carefully than the men---better still, have

none".

On

November 26 the Terra Nova sailed for Dunedin and

Port Chalmers. The Scotts did not sail with her but came

back in the harbor tug and spent their last two days

together walking over hills to Sumner. The next day, in the

afternoon, it was time to say farewell. There were massive

cheering crowds on the shore as a tug took off the three

wives. Wilson wrote of his wife, Ory, "There on the bridge I

saw her disappear out of sight waving happily, a goodbye

that will be with me till the day I see her again in this

world or the next---I think it will be in this world and

some time in 1912". Kathleen wrote, "I didn't say goodbye to

my man because I didn't want anyone to see him sad. On the

bridge of the tug Mrs. Evans looked ghastly white and said

she wanted to have hysterics but instead we took photos of

the departing ship. Mrs. Wilson was plucky and good...I

mustered them all for tea in the stern and we all chatted

gaily except Mrs. Wilson who sat looking somewhat

sphinx-like". The ship sailed at 4:30 p.m. on November 29,

1910. For most of the men it would be a year and a half

before they would see any green living thing; five others

would never return.

Other

than a little seasickness, the first few days at sea went

quite well. However, on December 2 they were hit by a huge

storm that dislodged the deck cargo creating dangerous

conditions topside. The seas crashed over the decks, tossing

the dogs from one side to the other, as water poured into

the engine room and cabins below. The ponies suffered the

most and when all was said and done, one dog had been lost

overboard while two ponies had been killed. Meanwhile, the

seawater mixed with coal dust thereby creating a sludge that

choked the bilge pumps. Water quickly rose to the furnaces

and, for the first time, the men were in fear of losing

their ship. The men finally resorted to using buckets to

bale the water out by hand. By morning the seas had begun to

settle down. By 10:00 p.m. that evening Williams and Davies

had succeeded in cutting a hole through the engine room

bulkhead which allowed Teddy Evans a big enough hole to

crawl through so he could reach the pumps. Standing up to

his neck in water, Teddy was able to clear the valves and

"To the joy of all a good stream of water came from the pump

for the first time".

Afterwards, Raymond Priestly wrote

that the ship at her worst would have given Dante a good

idea for another Circle of Hell "though he would have been

at a loss to account for such a cheerful and ribald lot of

Souls". Bowers wrote, "Under its worst conditions this earth

is a good place to live in". Wilson wrote, "I must say I

enjoyed it all from the beginning to end". I think this was

because he was one of the few who did not suffer from

seasickness! About ten tons of coal were lost, sixty-five

gallons of petrol and a case of biologists'

spirits.

On

December 8 the first berg was spotted and on the following

day, in latitude 65°8'S, the Terra Nova entered

the pack. For the next three weeks the ship had to be shoved

and bashed through a massive amount of ice, consuming a

great deal of precious coal in the process. On December 30

Scott wrote, "We are out of the pack at length and at last

one breathes again". On New Year's Day, 1911, Mount Erebus

came into view. They attempted to land at Cape Crozier,

where they had planned on setting up winter quarters, but

the seas were too rough. So, McMurdo Sound was their next

option. Rounding the northwest tip of Ross Island, they

proceeded down the coast past Cape Royds, Inaccessible

Island, and Cape Barne. When they arrived at the Skuary,

soon renamed Cape Evans, Scott, Evans and Wilson made the

decision to set up winter quarters. About a mile and a half

of ice lay between shore and open sea. On January 4 the

Terra Nova anchored to the ice and the unloading

began. The ponies were especially happy to finally be on

firm ground as they rolled and kicked in the

snow.

The

first two motor sledges were unloaded and immediately put to

work hauling stores to the new camp. As the third, and

largest, sledge was unloaded and hauled by twenty men

towards the shore, it decided to break through the ice and

sink in sixty fathoms of seawater. Scott blamed himself for

the tragedy as he was in a hurry to get the ship unloaded so

she could embark with Campbell and his crew for King Edward

VII Land.

The hut

went up rapidly: it measured fifty feet by twenty-five and

was nine feet to the eaves. It was insulated with quilted

seaweed, lined with matchboard, lit by acetylene gas,

provided with a stove and cooking range and divided into two

by a partition made of crates (including the wine) to

separate the men's from the officers' quarters. Within two

weeks the hut was built and occupied.

Before

starting on the depot-laying journey across the Barrier and

towards the Pole, Scott and Meares traveled the fifteen

miles south to revisit Hut Point. Scott was furious to find

a window had been left open. Snow had drifted in and frozen

into a solid block of ice. Scott knew that no one was to

blame other than Shackleton since he was the last to use the

hut when he had based at Cape Evans three years earlier.

Scott wrote, "It is difficult to conceive the absolutely

selfish frame of mind than can perpetrate a deed like

this...finding that such a simple duty had been neglected by

one's immediate predecessors disgusted me

horribly".

On

January 24 the depot-laying party got away, with all the

dogs and eight ponies, across the Glacier Tongue and on to

the Barrier. Two days later, Scott and a team of dogs went

back to the ship across the ice to say good-bye to

Lieutenant Pennell and his crew. Scott figured that by the

time they returned from the depot-laying, the Terra

Nova would have already deposited Campbell and his five

companions--Raymond Priestly, surgeon Levick, Browning,

Dickason and Abbott--somewhere in King Edward VII Land, and

would be on her return voyage to New Zealand. Also on board

were Griffith Taylor, Frank Debenham, Charles Wright and

Edgar Evans who were to do scientific work in the mountains

of Victoria Land.

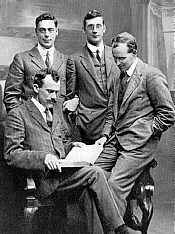

Standing: Debenham and

Wright; sitting: Taylor and Priestley

Two days later the

depot-laying party was on the Barrier, establishing a camp

far enough from its edge to be out of any danger of the ice

breaking free. They called this Safety Camp and it was from

here that they made their final plans for the push to the

Pole. The first doubts about the ponies came as they sank

into the soft snow and floundered. One of them actually went

lame and although a complete set of snow-shoes for the

ponies had been unloaded from the ship, all but one set were

left back at Cape Evans. The lone set of snow-shoes were

attached to "Weary Willie" with astounding results so Meares

and Wilson headed back to base camp for the others. When

they arrived at the Glacier Tongue, they found that all the

sea ice had broken away leaving no path to reach the camp at

Cape Evans.

Two days later the

depot-laying party was on the Barrier, establishing a camp

far enough from its edge to be out of any danger of the ice

breaking free. They called this Safety Camp and it was from

here that they made their final plans for the push to the

Pole. The first doubts about the ponies came as they sank

into the soft snow and floundered. One of them actually went

lame and although a complete set of snow-shoes for the

ponies had been unloaded from the ship, all but one set were

left back at Cape Evans. The lone set of snow-shoes were

attached to "Weary Willie" with astounding results so Meares

and Wilson headed back to base camp for the others. When

they arrived at the Glacier Tongue, they found that all the

sea ice had broken away leaving no path to reach the camp at

Cape Evans.

Meares and Wilson returned to Safety

Camp "shoeless" and on February 2 the party set forth with

five weeks' provisions, leaving behind two very disappointed

men: Atkinson with a sore heel and Crean to look after him.

They marched in an easterly direction until they arrived at

Corner Camp. At Corner Camp their first blizzard arrived

which kept them confined for three days. From Corner Camp

they marched due south for ten nights to make their final

depot. The ponies were becoming visibly weak, three in

particular. At Camp 11 Scott decided to send them back with

their escorts and push on with the remaining five. For the

next couple of days conditions worsened with heavy snow and

soon "Weary Willy", led by Gran, was overtaken by Meares and

Wilson with the dogs. The wolf in the dogs broke loose as

they pounced on the poor pony. The men were able to get them

off but not before the pony had been badly bitten. Next day

the ponies were able to proceed but at Camp 15, on February

17, Scott decided to turn back before reaching, as he had

hoped, the 80th parallel. At 79°28½'S, 142 miles

from Hut Point, they built a cairn and deposited more than

one ton of stores; this was One Ton Depot.

By this time Oates' nose had become

frostbitten as well as Bowers' ears and, besides, Scott

wanted to get back to Cape Evans to learn of any news left

by Pennell concerning Campbell's party at King Edward VII

Land. On the fourth day of the return trip, twelve miles

from Safety Camp, Wilson saw Meares' and Scott's dogs

disappear one after the other "exactly like rats running

down a hole--only I saw no hole. They simply went into the

white surface and disappeared". The sledge hung precariously

at the edge of the crevasse while eight dogs were left

dangling in the abyss, howling and struggling. Two of the

dogs had slipped their harness and fell forty feet to a

ledge where they curled up and went to sleep. Wilson and

Cherry-Garrard came to the rescue and hauled the eight dogs

out with great difficulty. There still remained the issue of

the two dogs left on the ledge, some sixty-five feet below.

Wilson protested but Scott insisted on being lowered into

the chasm to retrieve the dogs. As soon as the dogs were

hauled out, they engaged in a fight with Wilson's team.

Scott was left dangling in the abyss as the others rushed

off to separate the dogs. Finally, Scott was hauled in and

the next day they reached Safety Camp where they found Teddy

Evans, Ford and Keohane waiting for them. The three reported

to Scott that only one of the three ponies had survived the

return trip as the others had died from exhaustion. They

also had no news on Campbell, so after a meal and a few

hours of sleep they went on to Hut Point pulling the sledges

themselves.

When they reached the hut, they found

it to be empty. A note was pinned to the wall which said,

"Mail for Captain Scott is in bag inside south door" but

there was no bag and no mail. So, back they went to Safety

Camp where they found Atkinson and Crean with the mail.

"Every incident of the day pales before the startling

contents of the mail bag", Scott wrote. In the bag was a

letter from Victor Campbell. The Terra Nova had

sailed along the Barrier as far as King Edward VII Land but

found it impossible to go ashore. They turned back and on

February 3 sailed into the Bay of Whales only to find a

ship, anchored to the ice, which they recognized as the

Fram. Campbell, Levick and Pennell had breakfast in

the Fram and Amundsen, with two companions, had lunch

in the Terra Nova. Amundsen offered to give Scott

some dogs and Pennell offered to take the Fram's mail

to New Zealand. Amundsen reported that his attempt for the

Pole would not take place until the following Antarctic

summer.

As it

turns out, the Bay of Whales was the proper place for a

starting point on an attempt for the Pole. Scott was afraid

that too much was at risk to set up base camp at this

location: it was afloat and large chunks of it broke off

each year going out to sea. However, Amundsen knew that the

bay, charted by Ross in 1841, was still in the same position

when Borchgrevink landed there in 1900 and when Shackleton

sailed by in 1908 and named it the Bay of Whales. Besides,

the Bay was sixty miles closer to the Pole than McMurdo

Sound. Raymond Priestly was impressed when Amundsen drove

his dogs up next to the Terra Nova for lunch. When he

arrived next to the ship, he gave a whistle and the whole

team stopped as one dog. He turned the sledge upside down

and left the dogs in their tracks, to remain there, without

fighting, until he had finished his lunch. Dogs, plenty of

dogs, well-trained dogs was impressive. As much attention

was given the dogs as the men on the Fram: a false

deck had been built above the real one to protect the dogs

in stormy seas, an awning had been erected to protect them

from the sun, and their diet was a carefully balanced

mixture of dried fish, pemmican and lard.

When he read the news, Scott wrote,

"There is no doubt that Amundsen's plan is a very serious

menace to ours". Although Scott took the news in good

stride, many of the others were very angry and wanted to

march right into the Bay of Whales and have it out, once and

for all, with Amundsen. Cherry-Garrard wrote, "We had just

paid the first installment of making a path to the Pole; and

we felt, however unreasonably, that we had earned the first

right of way".

Scott

now had to get everyone back to Hut Point. On the last day

of February the move began with Meares and Wilson leading

off with the dog teams. Wilson went round by Cape Armitage

and arrived safely at Hut Point. The others followed with

the ponies and had to follow the sea-ice route. They had

barely started when "Weary Willie" collapsed and died. While

Scott, Oates and Gran stayed by Weary Willie's deathbed,

Bowers, Crean and Cherry-Garrard went on ahead with the four

surviving ponies and the loaded sledges. They dropped down

off the Barrier onto sea-ice and started to probe their way

round Cape Armitage. When the ponies could go no farther,

they camped and turned in but were aroused two hours later

by a strange noise.

When they stepped outside, it was

discovered that the ice had broke up and their camp was now

adrift on a floe. One of the ponies had disappeared and

survival seemed unlikely. The only hope was to take the

three remaining ponies and four sledges and "hop" from floe

to floe as they made their way back to the Barrier. Six

hours passed before they made it to the edge of the Barrier.

Using sledges as ladders, Scott and the others were able to

climb on to the Barrier but the ponies drifted away on their

floe as killer whales stood by. Scott replied, "Of course we

shall have a run for our money next season, but so far as

the Pole is concerned I have little hope". Next morning,

Bowers spotted the ponies' floe resting against a spur

jutting out from the Barrier. Bowers and Oates were able to

make their way out across the floes and reach the ponies.

Unfortunately, one pony immediately fell in so Oates had to

kill him with his pick-axe. Meanwhile, the other two ponies

were brought to the brink of safety. Both were hauled out

but one could not get to his feet. The pony would slip and

fall back into the water with each attempt and when the

killer whales showed up, Bowers shouted, "I can't leave him

alive to be eaten by those whales". Bowers grabbed the axe

and killed him. When all was said and done, only one pony

had survived. They had started their depot-laying journey

with eight ponies; they bot back to Hut Point with

two.

Now they

waited at Hut Point for the sea-ice to freeze over again so

they could continue on to Cape Evans. On March 15 they were

joined by the geologists, Griffith Taylor, Frank Debenham

and Charles Wright along with Petty Officer Edgar Evans who

had been exploring the western mountains in Victoria Land.

On April 11 Scott and half the party were able to get away

for Cape Evans, with the rest to follow. When they reached

the base they found the hut in good shape but one of the

ponies and another dog had died. That left ten ponies out of

the original nineteen. On April 23 the sun vanished beneath

the horizon for the last time until August. Scott wrote that

the sledging season had come to an end. That is, except for

one trip led by Wilson to Cape Crozier in search of birds.

The adventure is best told in a book written by

Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the

World.

A great

deal of scientific work was accomplished during the winter

at Cape Evans. Scott's diary is full of scientific data. He

was constantly thinking and observing as he went on solitary

walks, recording all things seen. He had a passion for

science and was sensitive to nature and beauty alike. His

spiritual growth was boundless..."There is infinite

suggestion in this phenomenon (the aurora)--mysterious--no

reality. It is the language of mystic signs and of

portents--the inspiration of the gods--wholly

spiritual--divine signalling". Needless to say, hours and

hours of preparation were put into the plans for the push to

the Pole. Always his thoughts came back to transport. During

the winter three more dogs died.

Six men

missing from the hut at Cape Evans were Victor Cambell and

his five companions who, having failed to get ashore on King

Edward VII Land, had been taken by the Terra Nova to

Cape Adare, where they established their base near

Borchgrevink's old camp. The "Eastern Party" had thus become

the "Northern Party". It had been arranged that the Terra

Nova would pick up Campbell's party from Cape Adare on

her return from New Zealand in early 1912. Geology, with

twenty-five-year-old Raymond Priestley in charge, was to be

the main pre-occupation, and surgeon Murray Levick was to

study birds and marine life. So, the winter at Cape Evans

passed. Scott celebrated his forty-third birthday with his

companions. Scott wrote, "They are boys, all of them, but

such excellent good-natured ones; there has been no sign of

sharpness or anger, no jarring note, in all these wordy

contests; all end with a laugh". A Discovery custom

Scott revived was the issue of the South Polar

Times.

The sun

returned on Victor Campbell's thirty-sixth birthday, August

23. Scott fixed the date of departure for the Pole as

November 1, 1911, at the latest. They couldn't start earlier

because the ponies would not survive the cold so, to fill in

the time, Scott, Bowers, Simpson and Edgar Evans left on

September 15 on "a remarkably pleasant and instructive

little spring journey" to the western mountains. It was

probably on this trip that Scott picked his companions for

the push to the Pole. Wilson was a given; Edgar "Taff"

Evans, too--the sterling sledger, strong as an ox; Bowers,

the only man Scott could rely on to grasp details and

remember them--"The greatest source of pleasure to me is to

realise that I have such men as Bowers and P.O. Evans for

the Southern journey".

At the

end of October, 1911, Scott called his men together to give

them some bad news. The expedition was under heavy financial

strain and had literally ran out of funding. Those men

capable of forgoing their salary for the coming year were

asked to do so. Some had already decided to return with the

Terra Nova when she called in the summer: Griffith

Taylor was expected back at his university, Ponting and

Day's work was finished while Clissold and Forde were in

poor health. Most of the others volunteered to stay another

winter even if they received no pay. Before the departure of

the Southern Party, Scott, like all the others, wrote to his

family and friends. He acknowledged in his letter to

Kathleen, "I don't know what to think of Amundsen's chances.

If he gets to the Pole it must be before we do, as he is

bound to travel fast with dogs, and pretty certain to start

early. On this account I decided at a very early date to act

exactly as I should have done had he not existed. Any

attempt to race must have wrecked my plan, besides which it

doesn't appear the sort of thing one is out for...You can

rely on my not saying or doing anything foolish, only I'm

afraid you must be prepared for finding our venture much

belittled. After all, it is the work that counts, not the

applause that follows". Scott wrote on the last page of the

diary that he left behind, "The future is in the lap of the

gods. I can think of nothing left undone to deserve

success". On November 1, 1911, the time came for the start

of his last journey.

The

first to leave Cape Evans were Day, Lashly, Teddy Evans and

Hooper with the motor sledges while the others with ponies

and dogs followed behind. One machine gave out just beyond

Safety Camp while the other had to be abandoned a mile

beyond Corner Camp. On November 1, ten men, each with a pony

and sledge, left Cape Evans in detachments: Scott, Wilson,

Bowers, Oates, Atkinson, Cherry-Garrard, Wright, Edgar

Evans, Crean and Keohane. Meares and Dimitri followed with

the dogs. Everyone else remained at Cape Evans to carry out

further exploration and research in Victoria Land. Scott

assumed the Terra Nova would return in January

bringing Victor Campbell and his Northern Party back to Cape

Evans whereby Campbell would take command.

The

distance from Hut Point to the Pole and back was 1766

statute miles. Every step of the way had to be marched on

foot, with or without skis. They traveled by night for the

benefit of the ponies. Temperatures never rose above zero

Farenheit. Fighting constant snowfalls, the team reached One

Ton Camp on the fifteenth day. There was a constant worry

that the ponies would give out and upon reaching Camp 20, on

November 24, the first pony was killed. Four camps later, on

December 1, the second pony was shot.

Depots

were made at regular intervals of roughly seventy miles,

each containing food and fuel for a week for the returning

parties. Scott wrote on December 3, "Our luck in weather is

preposterous...the conditions simply horrible". On December

5 they awoke to a blizzard. The temperature normally rose

just before and during a blizzard but in this case the

temperature rose exceptionally high resulting in melting

snow making everything wet. Scott wrote, "One cannot see the

next tent, let alone the land. What on earth does such

weather mean at this time of the year? It is more than our

share of ill-fortune, but the luck may turn yet". The wet,

warm blizzard kept them confined to their tents for the next

four days. (This event quite likely led to their deaths. If

they had not lost these four days they would have reached

One Ton Depot ahead of the blizzard that kept them pinned at

their last camp.)

On the third day of the blizzard Scott

wrote, "Resignation to misfortune is the only attitude, but

not one easy to adopt...It is very evil to lie here in a wet

sleeping-bag and think of the pity of it, whilst things go

steadily from bad to worse". On the fifth day the blizzard

let up enough for the men to break camp. They had to beat

the ponies as they floundered up to their bellies and,

Wilson wrote, "constantly collapsed and lay down and sank

down, and eventually we could only get them on five or six

yards at a time--they were clean done". They struggled for

eleven hours after which time the party camped. Five ponies

were shot, skinned and made into a depot. Wilson wrote,

"Thank God the horses are now all done for and we begin the

heavier work ourselves".

Two days later found them on the foot

of the Beardmore Glacier. After setting up the Lower Glacier

depot, Meares and Dimitri started back with the dogs and

mail. Day and Hooper had already turned back so a party of

twelve, divided into groups, set out to man-haul the sledges

up the glacier towards the summit 10,000 feet above.

(Amundsen was already there). The glacier is over 100 miles

long and in some places 40 miles wide. The struggle began

with each man pulling over 200 pounds through the soft snow

which they sank into nearly up to their knees. Some suffered

from snow-blindness as others stumbled into crevasses,

sledges and all. On December 13, the day before Amundsen

reached the Pole, in nine hours the party had advanced less

than four miles. Scott wrote, "I had pinned my faith on

getting better conditions as we rose, but it looks as though

matters are getting worse instead of better". Bowers wrote

that he had "never pulled so hard, or so nearly crushed my

inside into my backbone by the everlasting jerking with all

my strength on the canvas band round my unfortunate tummy".

The situation gradually improved as

they scaled the glacier and on December 20 Scott named the

first returning party: Atkinson, Wright, Cherry-Garrard and

Keohane. Scott had dreaded this moment as all had pulled to

the limit of their strength, but now four good men had to be

deprived of their just reward: the Pole. The next day the

men established Upper Glacier depot at 7,000 feet. After

completion, the first supporting party left for home and

reached Hut Point thirty-five days later on January 26,

1912. The two remaining groups went on with two sledges and

twelve weeks' supply of oil and fuel, pulling 190 pounds per

man. In Scott's group were Oates, Wilson and Taff Evans

while Bowers had Teddy Evans, Lashly and Crean. They went on

climbing for another sixteen days to reach their highest

altitude at 10,570 feet.

On Christmas day, with a strong wind

in their faces, they advanced seventeen-and-a-half miles.

The Christmas meal consisted of pony hoosh, ground biscuit,

a chocolate hoosh made from cocoa, sugar, biscuit and

raisins thickened with arrowroot, two-and-a-half square

inches each of plum-duff, a pannikin of cocoa, four caramels

each and four pieces of crystallized ginger. From here they

made remarkable marches of fourteen to seventeen miles a

day.

On January 3 Scott chose four men to

continue with him to the Pole and instructed the other three

to return. Bowers was brought into his tent and Teddy Evans,

Lashly and Crean would become the second returning support

party. Teddy Evans was very bitter about Scott's decision

but the rest of the crew knew it was a proper choice; aboard

ship he was of great help but on land he was a failure.

Wilson wrote, "I never thought for a moment he would be in

the final party". Bowers wrote, "Poor Teddy--I am sure it

was for his wife's sake he wanted to go. He gave me a little

silk flag she had given him to fly on the Pole". Lashly and

Crean were both in tears as the three men turned back at

87°32'S, at an altitude of 10,280 feet and 169 miles

from the Pole.

There

was no sign of the Norwegians as Scott and the others

followed Shackleton's route. On January 6 they crossed the

line of latitude where Shackleton turned back and were

farther south, as they believed, than any man had been

before. For the next few days the going was difficult. On

January 9 they stayed in their bags all day as a blizzard

roared outside. On January 10 they resumed their march, made

a depot of one weeks' provisions and reckoned they were only

ninety-seven miles from the Pole. On this day came the first

hint that everyone was growing tired.

Scott wrote, "I never had such

pulling; all the time the sledge rasps and creaks. We have

covered six miles, but at fearful cost to

ourselves...Another hard grind in the afternoon and five

miles added. About seventy-four miles from the Pole--can we

keep this up for seven days? It takes it out of us like

anything. None of us ever had such hard work before...Our

chance still holds good if we can put the work in, but it's

a terribly trying time". A day later "It is an effort to

keep up the double figures, but if we can do another four

marches we ought to get through. It is going to be a close

thing". Two days later, despite higher temperatures Scott

wrote, "It is most unaccountable why we should suddenly feel

the cold in this manner".

On

January 13 they crossed the 89th parallel. Next day they

started to descend and made their final depot of four days'

food. Scott wrote, "We ought to do it now". This was

the last cheerful entry in Scott's diary. The next day,

January 16, they made a good march and figured they would

reach the Pole the following day. In the afternoon, Bowers

spotted something ahead which looked like a cairn. Half and

hour later they realized the black speck to be a flag tied

to part of a sledge. Nearby was the remains of a camp along

with tracks made by sledges and dogs...many dogs. Scott

wrote, "This told us the whole story. The Norwegians have

forestalled us and are first at the Pole." Scott felt he had

let his loyal companions down and had utterly failed them.

Scott wrote, "Many thoughts come and much discussion have we

had...All the day dreams must go; it will be a wearisome

return".

On

January 17, a force five gale struck them along with

temperatures falling to fifty-four degrees of frost. Oates,

Evans and Bowers all suffered from severe frostbite as they

made an early lunch-camp. Scott wrote, "Great God! This is

an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured

to it without the reward of priority. Well, it is something

to have got here, and the wind may be our friend tomorrow".

Wilson wrote that it was "a tiring day" and despite Amundsen

having "beaten us in so far as he has made a race of it...We

have done what we came for all the same and as our programme

was made out".

The next morning they found the

Norwegian's camp about two miles away. Inside the tent was a

sheet of paper with five names on it: Roald Amundsen, Olav

Olavson Bjaaland, Hilmer Hanssen, Sverre H. Hassel and Oscar

Wisting. The date of the note was December 14, 1911. They

had taken twenty-one days less than Scott's party to reach

the Pole. They had arrived at the Pole with their dogs via a

glacier they had named the Axel Heiberg. On the day Scott

and his companions arrived at the Pole, Amundsen and his men

were only one week out from their winter quarters in the Bay

of Whales. The five men reached the Fram in the Bay

of Whales on January 25, 1912. In the Norwegian tent

Amundsen left a note for Scott and a letter to be delivered

to King Haakon. Bowers took photographs, and then they

marched seven miles south-south-east to a spot which put

them within half a mile of the Pole, altitude 9,500 feet.

Here they built a cairn, planted "our poor slighted Union

Jacks" and the rest of the flags, photographed themselves

and headed for home. Scott wrote, "Well we have turned our

back now on the goal of our ambition with sore feelings and

must face 800 miles of solid dragging--and goodbye to the

daydreams!"

At the Pole, L

to R: Wilson, Evans, Scott, Oates and Bowers

The return trip started out

fairly well but the temperatures were obviously becoming

colder. Scott wrote, "There is no doubt that Evans is a good

deal run down". On January 23 they had to camp early because

of frostbite to Evans' nose. Oates' feet were always cold

and when a blizzard held them up seven miles short of the

next food depot, Scott wrote, "I don't like the look of it.

Is the weather breaking up? If so God help us, with the

tremendous summit journey and scant food".

The return trip started out

fairly well but the temperatures were obviously becoming

colder. Scott wrote, "There is no doubt that Evans is a good

deal run down". On January 23 they had to camp early because

of frostbite to Evans' nose. Oates' feet were always cold

and when a blizzard held them up seven miles short of the

next food depot, Scott wrote, "I don't like the look of it.

Is the weather breaking up? If so God help us, with the

tremendous summit journey and scant food".

Despite the delays and difficult

travel, the marches were good. They were becoming very tired

as evidenced by the many injuries due to falls: Wilson

strained a leg tendon and had to limp painfully beside the

sledge for several days; Scott fell and bruised his shoulder

and Evans hand lost two fingernails. On February 7 they

reached the head of the Beardmore Glacier and the next day

they started their decent. On February 11, in difficult

conditions, they took a wrong turn and ended up in the worse

"ice mess" they had ever been in. For the next two days they

stumbled around in a maze of ridges, growing more weak and

despondent. They knew the next depot could not be far away

but they simply couldn't find it.

Down to their last meal, the men

accidentally came upon the depot which was shrouded in fog.

Scott wrote, "The relief was inexpressible. There is no

getting away from the fact that we are not pulling strong".

At this point it was determined to reduce rations since they

weren't making the distances between depots in a timely

manner. This only weakened them further as Evans began

losing heart and was "nearly broken down in brain, we

think". On February 16 Evans collapsed and camp had to be

made. Next day he felt better and said he could go on. He

would march for a while and then stop to adjust his boots

while the others went on. When he failed to catch up, the

others would go back only to find him kneeling in the snow

with a wild look in his eyes. His companions sledged him to

the next camp and soon after midnight he died.

After a few hours rest, they were on

their way again. At the foot of the glacier they reached the

pony meat and enjoyed their first full meal since leaving

the plateau. "New life seems to come with greater food

almost immediately". From here the travelling became

difficult as the snow became very soft. "Pray God we get

better travelling as we are not so fit as we were and the

season advances apace". They left the foot of the glacier on

February 19. On the 27th, Wilson's diary stopped. Bowers had

given up on his on January 25. They arrived at the Southern

Barrier depot six days later. Here they discovered a

shortage of oil, presumably due to evaporation from the

poorly sealed one-gallon tins. Another seventy miles brought

them to the Middle Barrier depot where they once again

discovered a short supply of oil.

By this time Oates could no longer

conceal his pain: his toes were black and gangrene was

setting in. Temperatures were down to -40°F and the

surface was so bad that even a strong wind in the sail would

not move the sledge. Scott wrote, "God help us, we can't

keep up this pulling, that is certain. Among ourselves we

are unendingly cheerful, but what each man feels in his

heart I can only guess". On March 7 Scott mentions the dogs

for the first time: "We hope against hope that the dogs have

been to Mt. Hooper (the next depot), then we might pull

through. If there is a shortage of oil again we can have

little hope...I should like to keep the track to the end".

On the same day, the dogs, driven by Cherry-Garrard and

Dimitri, were waiting at One Ton Depot, some seventy-two

miles from Mt. Hooper.

On March 9 Scott and his men reached

Mt. Hooper. "Cold comfort. Shortage on our allowance all

round...The dogs which would have been our salvation have

evidently failed". An unusual north-west wind kept them in

camp the next day as it was simply too cold to face. With

half-cooked food, all of them getting frostbitten, all

knowing they were doomed, they discussed the situation.

Months before, at Cape Evans, they had discussed what to do

if one of them became so injured as to not be able to

continue on. Wilson carried lethal doses of morphine and

opium in his medicine chest so one could eliminate himself

if the situation called for it. At this point Scott ordered

Wilson to hand over the drugs so Wilson handed each man

thirty opium tablets. They were never used as suicide was

against the code.

Things

got worse as the north wind continued to blow in their

faces. Wilson was now becoming weak so Scott and Bowers had

to make camp by themselves. The temperature fell to

-43°F. On March 16 or 17 (they lost track of the days)

Oates said he couldn't go on and wanted to be left in his

bag. The others refused and he struggled on. There was a

blizzard blowing in the morning when Oates said "I am just

going outside and may be some time" and he stumbled out of

the tent. Scott wrote, "We knew that poor Oates was walking

to his death, but though we tried to dissuade him, we knew

it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman".

Oates was never to be seen again.

On March 20 they awoke to a raging

blizzard. Scott's right foot became a problem and he knew

"these are the steps of my downfall". Amputation was a

certainty "but will the trouble spread? That is the serious

question". They were only eleven miles from One Ton Depot

but the blizzard stopped them from continuing on. They were

out of oil and had only two days' rations. "Have decided it

shall be natural--we shall march for the depot and die in

our tracks", wrote Scott. They did not march again and on

March 29 Scott made his last entry: "It seems a pity, but I

do not think that I can write more. R. Scott. For God's sake

look after our people". On another page he scribbled, "Send

this diary to my widow".

Remarkably, Scott was able to find the

strength, despite being half starved and three quarters

frozen, to write twelve complete, legible letters. He wrote

to Kathleen and Hannah, to his brother-in-law, to his naval

comrades Sir Francis Bridgeman and Sir George Egerton, to

the Reginald Smiths and to Sir James Barrie. To Barrie he

wrote, "I may not have proved a great explorer but we have

done the greatest march ever made and come very near to

great success".

He wrote to Oates' and Bowers' mothers

and to Wilson's wife. Wilson wrote to his parents, "looking

forward to the day when we shall all meet together in the

hereafter. I have had a very happy life and I look forward

to a very happy life hereafter when we shall all be together

again. God knows I have no fear of meeting Him--for He will

be merciful to all of us. My poor Ory may or may not have

long to wait". Letters were written to J. J. Kinsey in New

Zealand and Sir Edgar Speyer expressing regrets for leaving

the expedition in such a state of affairs, "But we have been

to the Pole and we shall die like gentlemen".

In Scott's letter to Kathleen, he

wrote of hopes for his son, "I had looked forward to helping

you to bring him up, but it is a satisfaction to know that

he will be safe with you...Make the boy interested in

natural history if you can. It is better than games. They

encourage it in some schools. I know you will keep him in

the open air. Try to make him believe in a God, it is

comforting...and guard him against indolence. Make him a

strenuous man. I had to force myself into being strenuous,

as you know--had always an inclination to be idle". As for

Kathleen, "I want you to take the whole thing very sensibly,

as I am sure you will...You know I cherish no sentimental

rubbish about remarriage. When the right man comes to help

you in life you ought to be your happy self again--I wasn't

a very good husband but I hope I shall be a good

memory...The inevitable must be faced, you urged me to be

the leader of this party, and I know you felt it would be

dangerous. I have taken my place throughout, haven't

I?...What lots and lots I could tell you of this journey.

How much better it has been than lounging about in too great

comfort at home. What tales you would have had for the boy,

but oh, what a price to pay. Dear, you will be good to the

old Mother...I haven't had time to write to Sir Clements.

Tell him I thought much of him, and never regretted his

putting me in charge of the Discovery".

Finally, there was a Message to the

Public. He explained how the expedition's disaster was not

due to poor planning, but by bad weather and bad luck. It

was no one's fault..."but for my own sake I do not regret

this journey, which has shown that Englishmen can endure

hardships, help one another, and meet death with as great a

fortitude as ever in the past. We took risks, we knew we

took them; things have come out against us, and therefore we

have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of

providence, determined still to do our best to the

last...Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the

hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which

would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These

rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale, but

surely, surely, a great rich country like ours will see that

those who are dependent on us are properly provided

for".

Even at

the very end Scott still felt comfortable with his decisions

and felt a need to defend that position when he wrote,

"Every detail of our food supplies, clothing and

depots...worked out to perfection...We have missed getting

through by a narrow margin which was justifiably within the

risk of such a journey". Death, to Scott, was not a failure

since they had reached their goal---the Pole. He hoped he

had set an example of courage and loyalty to all those left

behind when he wrote to Sir Francis Bridgeman, "After all we

are setting a good example to our countrymen, if not by

getting into a tight place, by facing it like men when we

were there".

The

blizzard raged on for another ten days before Scott's last

entry on March 29, 1912. It was not until November 12 that

Surgeon Atkinson, leader of the search party, found their

tent all but buried in snow. When "Silas" Wright pulled the

flap aside, they saw the three men in their sleeping bags.

On the left was Wilson, his hands crossed on his chest; on

the right, Bowers, wrapped in his bag. It appeared that both

had died peacefully in their sleep. But Scott was lying half

out of his bag with one arm stretched towards Wilson.

Tryggve Gran said, "It was a horrid sight. It was clear he

had had a very hard last minutes. His skin was yellow,

frostbites all over". Gran envied them. "They died having

done something great--how hard must not death be having done

nothing". Petty Officer Williamson said, "His face was very

pinched and his hands, I should say, had been terribly

frostbitten...Never again in my life do I want to behold the

sight we have just seen". At the age of forty-three, Scott

had been the last to die.

Atkinson

took charge of the diaries and letters and read aloud the

account of Oates' death and the Message to the Public. He

then read the Burial Service and a chapter from Corinthians

after which all the men gathered and sang Scott's favorite

hymn, "Onward Christian Soldiers". The tent was then

collapsed over the bodies and a snow cairn was built over

all. Placed on top was a pair of crossed skis. Here they

would lie until one day, drifting with the Barrier, they

would find their final resting place in the sea. Atkinson

led the search party back along the path believed taken by

Scott in hopes of finding Oates. They found his sleeping bag

but nothing more. Near the spot where they assumed he had

fallen, the men erected a cross with the following

inscription: "Hereabouts died a very gallant gentleman,

Captain L. E. G. Oates of the Inniskilling Dragoons. In

March 1912, returning from the Pole, he walked willingly to

his death in a blizzard to try to save his comrades, beset

by hardship".

The

expedition was expected back in New Zealand early in April

1913. In January, Kathleen set out to meet him by way of the

United States. After a few days of camping with cowboys in

New Mexico, she set out from San Francisco aboard RMS

Aorangi. On February 19, between Tahiti and

Raratonga, she was called to the captain's cabin. With

shaking hands, he showed her a message received by wireless:

"Captain Scott and six others perished in a blizzard after

reaching the South Pole January 18th".

She went into mental shock as she went

about her business the rest of the day: playing cards,

taking a Spanish lesson and discussing American politics.

Her brother Wilfrid met her in Wellington along with Ory

Wilson, Atkinson and Teddy Evans who had taken the Terra

Nova down to McMurdo Sound to embark Scott's party and

the rest of the expedition. Atkinson handed Kathleen her

husband's diary and last letter. It was now Kathleen's turn

to be courageous in the face of tremendous debt still owed